Today the real success of an advertising campaign can be reflected in

how memorable their campaign was. Coca – Cola’s musical ads, ‘I’d like to Teach

the World’, their reappropriation of Santa Claus from his original green out

fit to the Coke colours of red and white are instantly identifiable, ‘For Mash

get Smash’ or ‘It’s Martini’ are still fondly remembered. In the 1920’s the

print media was the main weapon of the advertisers to reach the public but in

the early part of the roaring Twenties, a new pretender to the advertising

crown was making it way to market, radio.

The Marconi company led the way with innovation in both transmitting and

receiving, producing the most popular ‘listening-in’ devices for the wireless. To

deliver their message, the Marconi Company used the newspapers and trade

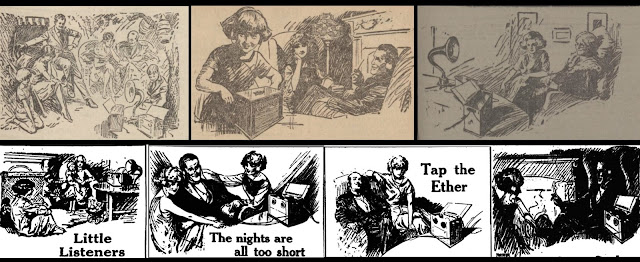

publications. In order that their products stood out from the crowd, in 1923

they commissioned a series of drawings used in newspaper ads encouraging

purchases of their radios sets. They showed how valuable they were to enrich

the lives of those who invested in the new medium.

They contracted an illustrator and artist to capture the ‘joy’ of radio

listening and his work created a sensation in the newspapers and for their

readers. Radio became a must have. The graphic illustrations, portrayed in an

art deco style were stylish, appealed to the emotions and illustrated how radio

could make like better. Advertisers were selling a dream; the world of radio was

elegant no matter where you were or what you did. Many of the Marconi portrayals

were of upper class people in decorative, modernist settings, creating a utopia

often far from the lives of working class post war Britons. The purchase of a

radio set was far beyond the financial reach of many of those who were still

recovering from the First World War. Homemade crystal sets were extremely

popular with working class listeners. Marconi’s advertisements exuded luxury

and created a theme that the new medium of radio would offer everything

including music, weather forecasting and information talks.

You can support our work with the price of a cup of coffee at KO-FI. Every little helps with research site payments and books purchased for future great radio history memories. Use the link button at the top of the blog.

The illustrations displayed a modern affluent Britain. The surroundings

are plush set in drawing rooms, with quality furniture and fittings. The men

are smartly dressed, with nearly all of them smoking a pipe or a cigar. The

women are drawn in elegant dresses and crafted hairstyles. The ballroom scenes

exude affluence and a rich lifestyle and spell the end of the live music era

replaced by music through the wireless. Radio is a unifier of the family unit

as the drawings feature parents and their children, even the children enjoying

the radio broadcasts with their grandparents. One depicts what appears to be a

teacher and her children outdoors being educated by the radio broadcasts. In

one scene a couple have gone to the country to have a picnic in their

automobile listening to the radio while the enjoyed their moment yet if you

look closely, they are not alone as another man watches on from the tree line.

The radio set is shown as the perfect accompaniment indoors or outdoors. The reality however for many living in the UK

in the early twenties, all of this high-brow living was aspirational.

By 1923, the British Broadcasting Company had just been formed and had

taken over the running of the various stations around Britain operated by

wireless set manufacturers. On 18 October 1922 the British Broadcasting Company

Ltd was incorporated with a share capital of £60,006, with cumulative ordinary

shares valued at £1 each and six major shareholders,

The shares were equally held by six companies:

·

Marconi's

Wireless Telegraph Company

·

Metropolitan

Vickers Electrical Company

·

Radio

Communication Company

·

The British Thomson-Houston Company

·

The General Electric Company

Marconi was at the heart of transmitting and

manufacturers radio sets. They wanted to cement their position at the forefront

of radio, in a crowded field of manufacturers. Harold Forster was employed to

produce a set of illustrations that would be used in the newspaper campaign for

their premier product ‘The Two Value Marconiphone’. The campaign, which was broadcast

at a national and local level, helped the Marconi Company maintain its lead as

the main seller of ‘listening-in’ sets in the UK. The illustrations used in the

advertisements had two different styles often used deliberately in the

publication they were placed in to appeal to various classes. The more

elaborate drawings appeared in national newspapers and trade publications, and

often as half page advertisements while the darker, less crowded portraits

appeared in regional newspapers.

Forster, in his late twenties in 1923, would have

an illustrious career as an illustrator and an artist. He did not confine

himself to the Marconi work, illustrating many products and brands. He was responsible for pre-war Black Magic

chocolate illustrations. He produced a number of the famous World War Two

posters commissioned by the British Government including the ‘Keep Mum, She’s

Not So Dumb’ and ‘Forward to Victory’ posters. He would also produce iconic

movie posters including for the Jack Hawkins action film, ‘Angels One Five’.