For over a century, a ‘fact’ has dominated

communications history but now doubts have weakened its veracity and we ask, is

any part of this historical story actually true? Has the wrong location and

country undeservedly received credit? It’s now time to address and correct these

inaccuracies.

The Fact: On December 11th 1901, Marconi

received the first trans-Atlantic wireless message when the Morse code ‘S’ was

sent from Poldhu in Cornwall to St. John’s Newfoundland.’

This is the commonly recognized fact in most

textbooks but is there any truth to it and more importantly was that message

really sent from Poldhu or has the Cornish town falsely claimed the heritage to

this event for over one hundred years?

The first question one needs to ask, is this. If

you were to travel across the Atlantic and you were unsure of the range of the

craft in which you were travelling as it had never completed the journey before,

would you want to travel 3,425km or 3,164Km? At almost 300km closer, the

shorter distance would provide the greatest opportunity for success. That distance

is a vital number in this story as the perceived truth unravels.

The Background

The desire to span the Atlantic by means of communications

gathered pace from the mid-19th century. With the invention of the telegraph,

attempts to lay an undersea cable connecting Europe and America began in the

1850’s. The first successful messages dispatched across the ocean were in 1858

from a telegraph office in Valentia, County Kerry to Trinity Bay, Nova Scotia.

The cable failed within weeks. Eventually finances were raised and the job was

completed in 1865 and 1866 but the cables were susceptible to bad weather,

damage, salt water and breakages which were often very expensive to locate and

repair. For the main ‘Anglo-American Telegraph Company’, messaging across the

Atlantic was a lucrative business as trade and global commerce increased

rapidly.

Marconi Invents and Disrupts the status quo.

Guglielmo Marconi was born in Bologna Italy in 1874. His

parents were an Italian merchant Guiseppe, who married for a second time,

following the death of his first wife, to Irish woman Annie Jameson, a member

of the famous whiskey distilling family. Marconi began his first experiments in

wireless telegraphy in his native Italy. His Irish mother encouraged the young

inventor, who was gathering ideas and information from many pioneers attempting

to harness the ether, to go to London. In London he was introduced to William

Preece, the chief engineer with the GPO. He saw huge advantage in wireless

communications and helped the young Italian demonstrate the ability and power

of the new medium.

While Marconi was the engineer, his cousin Henry Jameson

Davis saw huge financial prospects in the success of the wireless telegraphy.

In 1897, the formed the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company to raise finance to

protect Marconi’s patents and generate commercial possibilities for radio. Marconi

was a publicist in an era prior to Google searches and social media. He and

Jameson Davis were known to exaggerate or even falsify successes with

experiments to gain press attention and the interest of potential financial

backers.

Marconi needed to keep the British post office and UK

Government on his side to allow him to continue with the experiments and to

gain access to lucrative contacts and contracts. The British began to see huge

potential in wireless communications to maintain their grip on the Empire and

it’s position as the dominant nation on the planet. In 1898 following a

successful demonstration of radio to deliver sports journalism and news at Dun

Laoghaire (Kingstown Regatta), wireless telegraphy was demonstrated to the King

at the regatta in Cowes shortly after.

The Building of Poldhu & connecting it with Ireland

During

the next four months much work was done in modifying and perfecting the

wave-generating arrangements, and numerous telegraphic tests were conducted

during the period by Mr. Marconi between Poldhu in Cornwall, Crookhaven, in the

South of Ireland, and also with Niton in the Isle of Wight. A delay occurred

owing to a storm on September -18, 1901, which wrecked a number of masts, but

sufficient restoration of the aerial was made by the end of November, 1901, to

enable him to contemplate making an experiment across the Atlantic. He left

England on November 27, 1901, in the steamship ‘Sardinian’ for Newfoundland,

having with him two assistants, Messrs. Kemp and Paget, and also a number of

balloons and kites. He arrived at St. John's, Newfoundland, about December 5th.

(The Wireless Age Magazine)

According to Marconi,

‘In the design and construction of the

Poldhu station I was assisted by Sir Ambrose Fleming, Mr. R. N. Vyvyan and Mr.

W. S. Entwistle.’

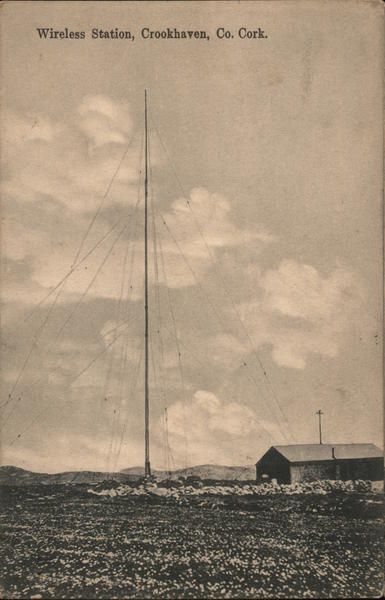

The Irish Leg at Crookhaven

By mid June, Marconi had built his new wireless station at

Brow Head near Crookhaven on the South West coast of Ireland. The County Cork

headland was Ireland’s most westly promintary. A one hundred and eighty foot

mast had been erected and a powerful transmitter installed to increase the

range of communications for ship to shore. When Marconi first arrived at the

small fishing port hundred turned out to welcome the wireless pioneer. Many of

those spectators were women hoping perhaps to catch the eye of the then

bachelor Marconi. His first experiment from the station was on June 16th

to contact the liner Lucania which was both en-route from New York across the

Atlantic and fitted with Marconi wireless equipment. A special train was

organised by the local Skibereen and Schull Tramway to bring a ‘record’ number

of spectators to Crookhaven to witness this breakthrough in communications.

According to the Southern Star newspaper ,

‘This event is no

doubt unique in the history of West Cork and we are certain that large numbers

will avail of the opportunity of witnessing this epoch making experiment’

Why Crookhaven?

Crookhaven already had been the epicentre of telegraphic

news. When the United States based Reuters news agency opened an office in

London in 1851, an office in Queenstown (Cobh) followed two years later. Up to

that stage in order to get the news scoop, reporters would travel precariously

on small currachs out to liners as they reached the Irish coast to get first

hands news from America and then make their way into Cork to file their stories.

With the arrival of Reuters, desperate to get an advantage over their

competitors including Hearst, they built a telegraph station in Crookhaven,

building a telegraph line to Cork City which was then linked to Dublin and

London giving the American news agency a four hour head start on other agencies

who were still using reporters making the dangerous passage to the Liners.

At the turn on the

twentieth century, the ionosphere was yet to be discovered and that radio

signals travelling long distances actually went upwards, bounced off the

ionosphere and back down to earth. Marconi believed at that time that signals

were linear and would use the ocean’s surface to conduct the signals over

distances. This had been the premise of Oliver Lodge in his early Wireless

Telegraphy experiments in Scotland, firstly crossing the Rover Tay and then

ambitiously planning to span the Atlantic, which never got off the ground. Ireland would later be

pivotal in the trans-Atlantic connection with the building of Marconi’s

powerful Clifden station.

On the opposite side

of the Atlantic, Marconi initially built a station at Wellfleet, Massachusetts

to communicate across the Atlantic but a storm destroyed the aerial array and a

new site had to be quickly chosen. Financial incentives took him north of the

border from the United States initially towards Nova Scotia before finally

settling at Signal Hill outside St. John’s, Newfoundland. In December 1901 he set sail for St. John's. He was under

pressure from shareholders and his growing ego to deliver on his promise that

wireless could commercially beat the undersea cable telegraph. He had been

heavily subsidized by his financial backers who saw huge profits in the trans-Atlantic

messaging. Marconi had with his travelling crew, a small stock of kites and

balloons to keep a single wire aloft in stormy weather.

A site was chosen on

Signal Hill, and apparatus was set up in an abandoned military hospital. A

cable was sent to Poldhu, requesting that the Morse letter " S " be

transmitted continuously from 3:00 to 7:00 PM local time.

On 12th December, 1901,

under strong wind conditions, a kite was launched with a long wire attached

beneath. The wind unfortunately carried it away. A second kite was launched.

The kite bobbed and weaved in the sky, making it difficult for Marconi to

adjust his new syntonic receiver which employed the new Italian Navy coherer. With

hindsight and today’s knowledge it is difficult to understand how Marconi

determined the frequency of tuning for his receiver.

‘The result was much

more than the mere successful realization of an experiment. It was a discovery

which proved that, contrary to the general belief, radio signals could travel

over such great distance a those separating Europe from America and it

constituted, as Sir Oliver Lodge has stated, an epoch in history’. (Marconi)

Marconi’s claim was,

‘On Monday, December

9th, barely three days after my arrival, I and my assistants began work on

Signal Hill. The weather was very bad and very cold. On the Tuesday we flew a

kite with 600 feet of antenna wire as a preliminary test, and on the Wednesday,

we had inflated one of our small balloons, which made its first ascent during

the morning. Owing, however, to the strength of the wind, the balloon soon

broke away and disappeared in the mist. I then concluded that perhaps kites

would answer better and decided to use them for the crucial test.

I had arranged with

my assistants in Cornwall to send a series of "S's" at a prearranged

speed during certain hours of the day. I chose the letter "S" because

it was easy to transmit, and with the very primitive apparatus used at Poldhu I

was afraid that the transmission of other Morse signals, which included dashes,

might perhaps cause too much strain on it and break it down. Mr. Entwistle, Mr.

George and Mr. Taylor were in charge of the English station at Poldhu during

the transmission of signals to Newfoundland.

The following day the

signals were reportedly again heard at Signal Hill, though not quite as

distinctly. According

to the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers,

‘Marconi's

ambition at the turn of the century to demonstrate long-distance wireless communication,

and develop a profitable long-distance wireless telegraph service, led to his

pragmatic proposal in 1900 to send a wireless signal across the Atlantic. He conceived

a plan to erect two super-stations, one on each side of the Atlantic, for

two-way wireless communications, to bridge the two continents together in

direct opposition to the cable company (Anglo-American Telegraph Company). For

the eastern terminal, he leased land overlooking Poldhu cove in southwestern

Cornwall, England. For the western terminal, the sand dunes on the northern end

of Cape Cod, MA at South Wellfleet, was chosen.

The aerial array

comprised of 20 masts arranged in a circle. The ring of masts supported a

conical aerial system of 400 wires, each insulated at the top and connected at

the bottom, thus forming an inverted cone. Vyvyan, the Marconi engineer who

worked on the 1901 experiment, when shown the plan, did not think the design

sound. He was overruled, construction went ahead, and both aerial systems were

completed in early 1901. However, before testing could begin catastrophe

struck, the Poldhu aerial collapsed in a storm on 17 September, and the South

Wellfleet aerial suffered the same fate on 26 November, 1901.

At Poldhu Marconi quickly

erected two masts and put up an aerial of 54 wires, spaced 1 metre apart, and

suspended from a triadic stay stretched between these masts. The aerial wires

were arranged fan shaped and connected together at the lower end.

‘The

antenna was driven by the curious two stage spark transmitter, previously

discussed. There were many problems in getting it to work at the high power

levels desired. Our principal concern here is the frequency generated by the

Poldhu station. The oscillation frequency is determined by the natural resonant

response of the antenna system, which includes the inductance of the secondary

of the antenna transformer T2, since in effect the antenna system is

a base-loaded monopole’.

Historians have also

speculated that the transmitter might also have radiated a high-frequency

signal as well, since an HF signal would have been more suitable for

transatlantic communications. If, according to Belrose, Marconi had used a thin

wire transmitting antenna at Poldhu, this antenna would indeed have radiated

efficiently at odd harmonics of the fundamental resonant frequency. But according

to Electrical engineers today that they must conclude therefore that the Cornish

based spark-transmitter system radiated efficiently only on the fundamental

oscillation frequency of the tuned antenna system, about 850 kHz.

When Poldhu had become operational,

it was communicating successfully with stations in France and Europe and more

importantly with Marconi’s new wireless station at Crookhaven in County Cork,

on the southern coast. Work on building Crookhaven began in the summer of 1901.

According to Marconi,

the publicist, he recounted,

‘Another similar

station was erected at Cape Cod in Massachusetts. By the end of August, 1901,

the erection of the masts was nearly completed when a terrific gale swept the

English coasts, with the result that the masts were blown down and the whole

construction wrecked. I was naturally extremely disappointed at this unforeseen

accident, and for some days had visions of my test having to be postponed for

several months or longer, but eventually decided that it might be possible to

make a preliminary trial with a simpler aerial attached to a stay stretched

between two masts 170 feet high and consisting of sixty almost vertical wires.

By the time this aerial was erected another unfortunate accident, also caused

by a gale, occurred in America, destroying the antenna system of the Cape Cod

station.

I then decided,

notwithstanding this further setback, to carry out experiments to Newfoundland

with an aerial supported by balloon or kite, as it was clearly impossible at

that time of the year, owing to the wintry conditions and the shortness of the

time at our disposal, to erect high masts to support the receiving aerial. On

the twenty-sixth of November, 1900, I sailed from Liverpool accompanied by my

two technical assistants, Mr. G. S. Kemp and Mr. P. W. Paget.

We landed at St.

Johns, Newfoundland, on Friday. December the sixth, and before beginning

operations I visited the Governor, Sir Cavendish Boyle, and the Prime Minister.

Sir Robert Bond, and other members of the Newfoundland government, who promised

me their heartiest cooperation in order to facilitate my work. After taking a

look round at the various sites, I considered that the best one was to be found

on Signal Hill, a lofty eminence overlooking the harbour. On the top of this

hill was a small plateau which I thought suitable for flying either balloons or

kites. On a crag of this plateau rose the Cabot Memorial Tower and close to it

was an old military barracks. It was in a room of this building that I set up

my receiving apparatus in preparation for the great experiment.’

The newly constituted

Marconi company knew that they were not the only Wireless Telegraph company

attempting to span the Atlantic but they certainly wanted to be first and the

newspapers were following the build up to the attempt on both sides of the

Atlantic. Marconi knew that Professor Fessenden in the United States was making

great strides and had the Atlantic in his sights as has Sir Oliver Lodge in the

UK although unlike Marconi, Lodge’s plans were engineering based, while Marconi

saw the commercial possibilities of being both first and the most successful to

transmit across the Atlantic connecting London and New York.

According to Marconi,

‘On the morning of

Thursday, the twelfth of December, the critical moment for which I had been

working for so long at last arrived, and, in spite of the gale raging, we

managed to fly a kite carrying an antenna wire some 400 feet long. I was at

last on the point of putting the correctness of my belief to the test! Up to

then I had nearly always used a receiving arrangement including a coherer,

which recorded automatically signals through a relay and a Morse instrument. I

decided in this instance to use also a telephone connected to a self-restoring

coherer, the human ear being far more sensitive than the recorder.

Suddenly, at about

half-past twelve, a succession of three faint clicks on the telephone,

corresponding to the three dots of the letter S, sounded several times in my

ear, beyond the possibility of a doubt. I asked my assistant, Mr. Kemp, for

corroboration if he had heard anything. He had, in fact, heard the same signals

that I had.

I then knew that I

had been justified in my anticipations. The electric waves which were being

sent out into space from Poldhu had traversed the Atlantic, unimpeded by the

curvature of the earth which so many considered to be a fatal obstacle, and

they were now audible in my receiver in Newfoundland. I then felt for the first

time absolutely certain that the day when I should be able to send messages

without wires or cables across the Atlantic and across other oceans and,

perhaps, continents, was not far distant. The then enormous distance, for

radio, of 1,700 miles had been successfully bridged.’

But had the Atlantic been bridged and if it had, was it from Poldhu or

Crookhaven?

At the turn on the

twentieth century, the ionosphere was yet to be discovered and that radio

signals travelling long distances actually went upwards, bounced off the ionosphere

and back down to earth. Marconi believed at that time that signals were linear

and would use the ocean’s surface to conduct the signals over distances. This

had been the premise of Oliver Lodge in his early Wireless Telegraphy

experiments in Scotland, firstly crossing the Rover Tay and then ambitiously

planning to span the Atlantic, which never got off the ground. Ireland would later be pivotal in the trans-Atlantic

connection with the building of Clifden.

Initially Marconi

built a station at Wellfleet, Massachusetts to communicate across the Atlantic

but a storm destroyed the aerial array and a new site had to be chosen. A site was chosen on

Signal Hill, and apparatus was set up in an abandoned military hospital. A

cable was sent to Poldhu, requesting that the Morse letter " S " be

transmitted continuously from 3:00 to 7:00 PM local time.

On 12th December, 1901,

under strong wind conditions, a kite was launched with a 155 m long wire. The

wind carried it away. A second kite was launched with a 152.4 m wire attached.

The kite bobbed and weaved in the sky, making it difficult for Marconi to

adjust his new syntonic receiver which employed the Italian Navy coherer.

"Difficult" I will accept, but how he determined the frequency of

tuning for his receiver is a mystery to me. Whatever, because of this

difficulty, Marconi decided to use his older untuned receiver. History has

assumed that he substituted the metal filings coherer previously used with this

receiver for the newly acquired Italian Navy coherer, but Marconi never really

said he did. He referred only to the use of three types of

coherers.

‘The result was much

more than the mere successful realization of an experiment. It was a discovery

which proved that, contrary to the general belief, radio signals could travel

over such great distance a those separating Europe from America and it

constituted, as Sir Oliver Lodge has stated, an epoch in history’

Marconi celebrating

his own success.

Then Marconi’s claim

was,

‘On Monday, December

9th, barely three days after my arrival, I and my assistants began work on

Signal Hill. The weather was very bad and very cold. On the Tuesday we flew a

kite with 600 feet of antenna wire as a preliminary test, and on the Wednesday

we had inflated one of our small balloons, which made its first ascent during

the morning. Owing, however, to the strength of the wind, the balloon soon

broke away and disappeared in the mist. I then concluded that perhaps kites

would answer better and decided to use them for the crucial test.

I had arranged with

my assistants in Cornwall to send a series of "S's" at a prearranged

speed during certain hours of the day. I chose the letter "S" because

it was easy to transmit, and with the very primitive apparatus used at Poldhu I

was afraid that the transmission of other Morse signals, which included dashes,

might perhaps cause too much strain on it and break it down. Mr. Entwistle, Mr.

George and Mr. Taylor were in charge of the English station at Poldhu during the

transmission of signals to Newfoundland. On the following day the signals were

again heard, though not quite as distinctly. However, there was no further

doubt possible that the experiment had succeeded.’

The experiments were suddenly brought to a halt when the

Anglo American Telegraph Company sought a legal restraint claiming that he was

interfering with their exclusive contract to telegraph connections across the

Atlantic, as they controlled the majority of the undersea cables connecting

Newfoundland and Nova Scotia with Ireland and then onto Europe.

Crookhaven

According to the IEEE,

‘Despite

the crude equipment employed, and in our view the impossibility of hearing the

signal, Marconi and his assistant George Kemp convinced themselves that they

could hear on occasion the rhythm of three clicks more or less buried in the

static, and clicks they would be if heard at all, because of the low spark

rate. Marconi wrote in his laboratory notebook: Sigs at 12:30, 1:10 and 2:20

(local time). This notebook is in the Marconi Company archives and is the only

proof today that the signal was received.’

Marconi himself has been

evasive concerning the frequency of his Poldhu transmitter. Fleming in a

lecture he gave in 1903 said that the wavelength was of 1000 feet or more, say,

one-fifth to one-quarter of a mile (820 kHz is the generally quoted frequency).

Marconi remained silent on this wavelength, but in 1908 in a lecture to the

Royal Institution he quotes the wavelength as 1200 feet. But in 1901, anyone

who believed that they could, and did, believed so as an act of faith based on

the integrity of one man – Marconi.

‘The

antenna was driven by the curious two stage spark transmitter, previously

discussed. There were many problems in getting it to work at the high power

levels desired. Our principal concern here is the frequency generated by the

Poldhu station. The oscillation frequency is determined by the natural resonant

response of the antenna system, which includes the inductance of the secondary

of the antenna transformer, since in effect the antenna system is a base-loaded

monopole’.

CONCLUSION

The first trans-Atlantic wireless telegraph message

was received at Signal Hill from Crookhaven, Cork in Ireland. Not Poldhu.

Despite skepticism by many historians and electrical engineers, I believe that

Marconi did manage to span the Atlantic with a message through the ether using

wireless telegraphy but perhaps this success was accidental, not realising his

signals were being deflected by the ionosphere. But I do not subscribe to the

‘fact’ that the signal across the Atlantic emitted from Poldhu in Cornwall and

arrived on the opposite side of the Atlantic at St. John’s. In fact the truth

is that Poldhu tapped out the letter ‘s’ as Marconi requested but rather than

reaching Newfoundland it was picked up in Crookhaven (perhaps as planned) and

retransmitted from Crookhaven to Signal Hill, St. John’s. Therefore the first

transatlantic message was not Poldhu to St. John’s but Crookhaven to St. Johns,

Ireland to Canada rather than England to Canada. Whether this was the actual

plan, is not lost in the fog of time but if it was Marconi’s belief that the

oceans would conduct his signal, then the inference is that he would transmit

between the two closest points, Crookhaven and St. John’s. It was also winter

and the seas were unpredictable and rough, which would be another excellent

argument for broadcasting between the two closets points in his network of

wireless stations.

The origin of the transmission being designated as

coming from Poldhu would have been important for investors and attracting others.

It would demonstrate that the invested cash was being put to good work. For it

to be commercially successful, a service from the UK mainland to the United

States would be far more valuable than Ireland to the United States. If the

transmission success was from Poldhu it would rule out the middle man, Ireland,

and speed up the time of message transmission from London to New York. This

would be valuable in tackling the success of the undersea cable telegraph

companies.

In Orrin Dunlap’s book, ‘Marconi, The Man and his Wireless’,

which celebrated the work of the Irish-Italian inventor and entrepreneur, he

referred to and quoted fellow wireless telegraphy pioneer Sir Oliver Lodge.

Lodge, a competitor of Marconi, wrote in his own book ‘Talks About Wireless’

published in 1925, recounting the event of the first trans-Atlantic

communication, that,

‘When Signor Marconi

succeeded in sending the letter ‘S’ by morse signals from Cornwall to Ireland

to Newfoundland, it constituted an epoch in human history, on its physical side

and was an astonishing and remarkable feat’

The first public two-way wireless telegraph

communication happened on January 19th, 1903 when a message from US President

Theodore Roosevelt at the White House was transmitted via Morse code and sent to King Edward VII at

Buckingham Palace in England, who in turn responded to Roosevelt.

That day, US newspaper 'The Evening World', published that “Word is Flashed from Roosevelt to King

Edward” as it reported that Guglielmo Marconi and his team successfully sent

the first transatlantic radio transmission from the US. Marconi and his

assistants, Kemp, Taylor, Sargent, and Bradfield, were reportedly surprised

that the message was received and deciphered on the first attempt. Trans-Atlantic was a

reality and here to stay.

‘Fessenden and

Marconi: Their Differing Technologies and Transatlantic Experiments During the

First Decade of this Century’ by John S. Belrose lecture for the International

Conference on 100 Years of Radio -- 5-7 September 1995

Sources

https://worldradiohistory.com/

The Irish Newspaper Archives

The British Newspaper Archives

The US Library of Congress

Marconi & Ireland , Sexton UCC

Orrin Dunlap 'Marconi & His Wireless'

The Marconi Archives

Cambridge University Libraries

Oliver Lodge 'Talks About Wireless'

The Irish Pirate Radio Archive

The Wireless Age magazines.