Chris Cary who passed away in 2008 is famous in Ireland as the man who revolutionised Irish Radio with perhaps the greatest ever station to broadcasting in Ireland, Radio Nova (1981 -86). He was famously known as Spangles Muldoon during his days on Radio Caroline out in the North Sea but on land he fell foul of the law in 1968 and 1969 when raids in London by the GPO detectors closed Radio Free London in August 1968. The following are some newspaper reports of both the raid and the subsequent court case.

Support Irish Radio History Archiving

Irish Pirate Radio Recordings

Thursday, 5 December 2019

Chris Cary / Spangles Muldoon 1968

Chris Cary who passed away in 2008 is famous in Ireland as the man who revolutionised Irish Radio with perhaps the greatest ever station to broadcasting in Ireland, Radio Nova (1981 -86). He was famously known as Spangles Muldoon during his days on Radio Caroline out in the North Sea but on land he fell foul of the law in 1968 and 1969 when raids in London by the GPO detectors closed Radio Free London in August 1968. The following are some newspaper reports of both the raid and the subsequent court case.

Wednesday, 30 October 2019

The 15-24 Market Have Abandoned Irish Radio

With the release recently of the years JNLR figures for October 2018 - September 2019 there must be some concern within the industry in Ireland as the 15 -24 year old age grouping has abandoned the medium as newer platforms. The JNLR figures does not take account of some stations that are not in the JNLR sweeps including Spirit Radio and Christmas FM, nor does it include those who listen via station apps or apps like Ireland Radio and Tunein. But in the battle for the advertising euro this is a worrying trend in seven years.

In Dublin and the greater Dublin area there has been almost a 20% decline in young listeners who now prefer Spotify or online stations like the current Halloween FM. There is also the persistent issue of pirate radio stations broadcasting dance music not heard on licensed radio. The effect has been felt even by stations that clearly market themselves as for a younger generation. Over the same period Spin 1038 has seen a 9% decline while crucially FM 104, the city's market leader has seen a 14% decline in the 15-24 year old statistics. The only station that has seen similar year on figures or slight modest gains of less than 2% has been RTE 2 FM.

While the Cork numbers for the 'Listened Yesterday' in the 15-24 group was down 8%, the Cork 96FM/C 103 group were down 13% while Red FM was down 4%. There is no doubt as habits of the younger listener changes and the market fragments, the traditional stations are going to struggle more to attract and maintain listenership. For many younger listeners the stations have lost spontaneity as repetitive playlists and voice tracking have alienated that generation of listeners.

Listened Yesterday 15-24 Year Old

National Dublin Cork South South North N. East Multi- Dublin

East West West & Mid City Commuter

2011-2012 80 76 84 78 86 84 77 80 77

2018 - 2019 70 57 76 73 77 82 69 65 59

-10% -19% -8% -5% -9% -2% -8% -15% -18%

2011-2012 80 76 84 78 86 84 77 80 77

2018 - 2019 70 57 76 73 77 82 69 65 59

-10% -19% -8% -5% -9% -2% -8% -15% -18%

Donegal Radio Pirates in the 1940s

Donegal has had a rich pirate radio history especially due to its proximity to the Northern Ireland border and the city of Derry. But the county's spot in pirate radio history stretches back to the early days of radio. Here are two stories from that early period.

In 1945, as the Second World War ended and the Emergency as it was known in Ireland was wound down, Radio Nuala was reported to be broadcasting on medium wave from the Beehive public house in Ardara in Donegal. Part of their complaint was that the Radio Eireann signal was poor in the area and that they were being 'bombarded' by the signals of the BBC's Six Counties Service.

Some years later in 1947 a row between Donegal fishermen and a private fishery business about who had the rights to fish on the Irish side of the River Foyle from the Sea to Lifford would end with a High Court Case. The local fishermen in an attempt to raise the finance to fight the case in Dublin and to highlight the issue within the community operated a mobile radio service to broadcast their message. They even managed to cross the border briefly to broadcast in Strabane in County Tyrone

.

Labels:

2RN,

BAI,

Donegal,

Fianna Fail,

free radio,

pirate radio,

Radio,

ulster

Tuesday, 29 October 2019

An Irish Pirate Radio Pioneer - AN OBITUARY

In July 2019, the esteemed

and world renown pioneer of renewable energy Professor Godfrey Boyle passed

away. But not only was Mr. Boyle the professor emeritus of renewable energy and

the director of the Energy and Environment Research Unit in the Open

University's Faculty of Mathematics, Computing, and Technology, he was a

pioneer in pirate radio broadcasting.

On a number of pirate

radio forums there was some scepticism and questioning that a pirate radio

station could broadcast from a telephone box, but Professor Boyle and his then

student friends were the pirates behind these broadcasts.

In February 1968, using a

homemade transmitter, a tape recorder and an aerial attached from the roof of

the phone box to a nearby tree, their station was on the air broadcasting from

the corner of Lennoxvale and Malone Road in Belfast (there is a telephone box still located on the site). The tape recording began

with "You are now listening to an illegal broadcast and are committing an

offence under the Wireless Telegraphy Act. We will now allow you a few

minutes to switch off.' The operators knew and indeed hoped that it would be discovered by officials

from the detection unit of the GPO in Belfast and used it as a publicity stunt

in an attempt to liberalise the airwaves in Belfast. Their station broadcasting on 242m was known as Radio SRCIS and these initial broadcasts began a cat and mouse game with the authorities throughout 1968.

The Belfast Telegraph

reported that

‘No

action likely over kiosk radio THE GPO were to-day investigating the finding of

pirate radio equipment in a Malone Road telephone kiosk, but there is a

possibility they may decide to drop the whole matter. A spokesman said to-day:

"If this is the end of the illegal transmissions I doubt if we will pursue

our inquiries. But if it should start again, we would have to give the matter

further thought." The transmitting equipment. including a tape recorder

and aerial wire extending from the kiosk to a tree, was discovered by engineers

who toured the city yesterday using monitoring equipment. According to the

spokesman, the equipment found in the 'phone box was a lot of "old

stuff" of little value. It was probable the GPO would dispose of it.’

The incident was even raised in the British House of Commons when Sir Knox Cunningham, MP for South Antrim asked the British Postmaster-General Edward Short what steps would be taken to prevent the use by radio pirates of Post Office equipment in Ulster. The PMG replied "The apparatus was traced and removed by Post Office engineers" and added. "I do not propose to take any special precautions against a repetition".

Not deterred by the loss

of their transmitter Mr. Boyle and his fellow students at Queens University

just a short distance from Malone Road set up a rag week pirate station in

March. Broadcasting on 235m, Rag Radio was on the air. The station’s signal was

heard over three miles from the station’s transmitter located near the

University. At one stage the police laid siege to the Students Union headquarters

in the mistaken belief that the pirate transmitter was located there.

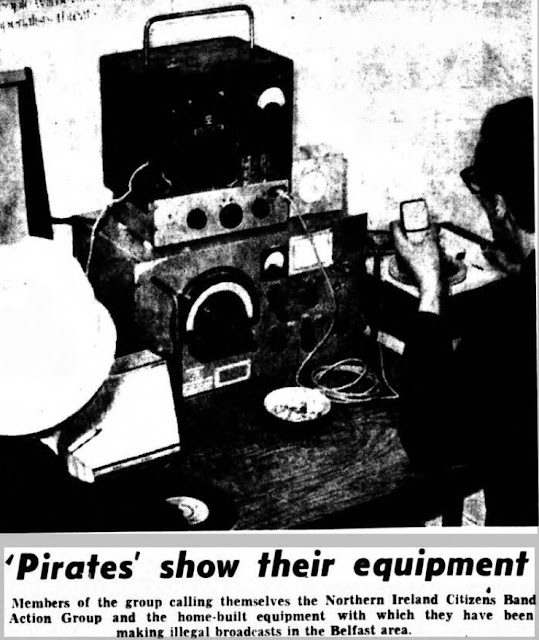

On April 19th 1968, the

Belfast Telegraph under the headline ‘Ulster Radio Pirates, A Year on the Air’

reported that,

‘Northern

Ireland’s radio "pirates" were on the air again last night and to-day

a spokesman disclosed that they have been making illegal broadcasts in the

Belfast area sporadically for a year. It is now believed that five or six young

men in their twenties, mostly students, are behind the broadcasts and that

their equipment is home-built. "The broadcasts began as series of

experimental transmissions by people interested in radio. Then we formed the

idea that we should be allowed to make broadcasts legally." said the

spokesman for the group who. call themselves the Northern Ireland Citizens'

Band Action Group. Recent broadcasts have mixed records with demands for new

wireless telegraphy legislation to make available a waveband for the use of private

citizens and to set up commercial stations. The spokesman claimed that the

situation which allows the Government-run BBC radio monopoly is undemocratic.

"People are entitled to run their own newspapers as a means of

communication and there are commercial television stations. Why not commercial

radio?" He said that incident' some weeks ago when transmission equipment

was found in a phone box on the Malone Road was designed to draw attention to

their ideas.’

Professor Boyle was born

in Brentford, West London, to Kevin Boyle, a quantity surveyor, and his wife,

Phyllis. The family moved to Belfast when Professor Boyle was a baby where he

and his sister, Mary, grew up. His early education was at St Malachy’s college before

he enrolled for an electrical engineering degree at Queen’s University Belfast,

where he ran societies, published alternative magazines, and was part of radical

activities in the University in a province that was on the brink of the

Troubles. In 1975 his influential book ‘Living

on the Sun’ was published, which advanced the then novel idea that industrial

countries could make a transition to renewable power.

Professor Godfrey Boyle,

a pirate radio pioneer, May He Rest In Peace

Wednesday, 16 October 2019

1930's Irish Radio Analysis - Part Five. It's All About The Money

2RN, the fledgling

Irish radio station stuttered to the end of nineteen twenties and into the

thirties still only clearly audible on the east of the country. There were many

problems encountered by the fledging radio station not least that lack of

finance provided from the exchequer. Many of those in Government feared the

power of radio and believed limiting the stations output would keep it in line.

At the time Ireland did not

produce any radio receivers of its own and all wireless sets were imported mostly

from the Britain UK

‘The Irish Free State was Great Britain

These imports however

were subject to a 33% import tax putting the price of a quality radio set

outside the reach of most Irish people. If you could not afford an imported

set, a homemade crystal set was the only option. With 2RN only audible on the

eastern side of the country, the use of radio west of the Shannon

was limited. This was reflected in the uptake of the required wireless licence.

The radio licence was introduced in 1923 and initially cost £1 but this was

reduced to 10s in August 1926 with the launch of 2RN in 1926 with a dearer

licence required for institutions such as hotels. In 1923 there was 1,020

licenses issued, 1,493 in 1926 the year 2RN began and in 1929 there were 7,660

licences in the Free State

The 1930’s there

was a boom in licences and an increased effort by the Government to detect

evaders. In 1930 just over 26,000 licenses were issued and the increased

numbers of radio sets purchased in advance of the 1932 Eucharistic Congress and

the launch of the powerful Athlone transmitter by 1934 there were 60,192 sets

licensed and by the end of the decade there were 166,275 licenses across Ireland

In 1935 the total

number of radio licences in the twenty six counties was 78,627 which equated to

one in every thirty eight citizens over eighteen having a licence. This figure

would increase to one in seventeen by 1939. The distribution of those licences

illustrated the divide in the nation when it came to radio. Leinster 60.03%, Munster 27.09%, Connacht 8.30% and Ulster Northern Ireland

at the end of April 1934 was 59,032 while in the entire 26 counties of the Irish Free State there were 51,667. In the six counties

in 1935 there were 63,000 licenses at ten schillings per licence.

The comparisons

with programming from the BBC often appeared in newspapers, magazines and in

political debate. The poor quality of output from the Irish State

2RN BBC

Programmes 45% 65%

Salaries 28% 7%

Maintenance 10% 19%

Overheads 17% 9%

It should be noted

in the maintenance costs the BBC had over thirty transmitters in 1930 while 2RN

only had Dublin and Cork

Finance was always

a concern for Irish Broadcasting. In 1930 the Government announced that it cost

£28,259 to run the station plus a further £47,000 set aside for the launch of

the new Athlone station. Income for the station was listed as £13,365 for the

licence fees, £30,700 from the tax on the imported radio receivers and just £40

from advertising. Advertising consisted of five minute ‘talks’ at the end of

programming at night. But in 1930 a new form of advertising was tested on the

urgings of the radio industry much of it through the weekly magazine The Irish

Radio News which had replaced the Irish Radio Review. Despite this apparent

lack of income, in 1930 the Secretary at the Department of Posts and Telegraphs

M.R. Heffernan TD wrote in an article aimed at improving listenership amongst

the rural community,

‘Let me make it quite clear that so far broadcasting in the Irish Free State has not cost the taxpayer a penny. It is

the other way about in fact. The broadcasting enterprise has actually

contributed in a small way towards the funds of the national exchequer.’

Radio Eireann had

spotted an opportunity to sell some of its airtime for sponsored programming.

The bulk of the ‘advertising’ consisted of five minute ‘talks’ broadcast at the

end of transmissions each weekday and solely for Irish made products. The

Government decided to sell the hour from 9.30 – 10.30 to sponsors and it was

divided into three twenty minute segments and from earning £220 in total advertising

revenue in 1932, a year later the station had earned £22,000 from sponsored

advertising, a lifeline for the cash strapped station. Unfortunately for the

station its new found wealth came at a price as the Government reduced the

percentage of the licence fee paid to the station.

,

1930's Irish Radio Analysis - Part Four. The Irish Language More Than a Cupla Focail

For an Irish radio

station it was not until 1937 before the station became familiarly known in the

Irish Language as Radio Eireann prior to that it was known as 2RN or Radio

Athlone which upset Irish language activists. Despite the constant effort by

these activists to force the Irish language centre stage by and the call for

more native language programmes on the State station it would not be until 1939

before the first GAA hurling match between Limerick

and Kilkenny would be broadcast entirely in the Irish language. All the more

remarkable when we learn that a year earlier the first all Irish pantomime had

been broadcast from Galway .

From the first

inception of Irish radio, there was a battle by Irish Gaelgoirs to use the

medium to rejuvenate and reinvent the Irish language and utilise the national

aspects of the stations availability. English was the predominant language in Ireland

In the early days

of Irish radio the Irish language supporters believed that the airwaves were

not being used properly for the promotion of the native language. Activists

initially wanted the state run station to be solely broadcast in Irish and that

it should support National ideals and traditions but there was very little

support from the political establishment who were unsure how to treat the new

medium and were suspicious of the intentions of traditionalists. Over eighty

percent of the station’s output was in English, the language of Government and

the Irish language did not even make up the entire remainder as French, German

and Esperanto all received significant airtime. Less than half of all music

played on the new station was Irish traditional and this caused much debate in

the newspapers of the day.

It was not until

1970 that a group of activists crowded into a small caravan in Galway and asserted their right to have a dedicated Irish

language radio station on the air. Two years after those pioneering pirate

broadcasts Radio na Gaeltachta took to the airwaves and has been broadcasting

nationally ever since. In recent years other stations have provided programming

in the native tongue including Radio Na Life, Radio Failte and local community

stations across the country. These have been augmented in recent years by

internet based Irish language radio stations. In 1989 when the Independent

Radio and Television Commission perused proposals for the new commercial

national franchise there was derision in the media when former pirate broadcaster

Chris Cary (Radio Nova) in his submission advanced his proposal for an Irish

language ‘word of the day’. This English born entrepreneur seemed unable grasp

the importance of the native tongue on a national stage but fast forward twenty

years and the national franchise now Today FM offers a thirty second occasional

slot ‘creid é no ná creid é’ not far off Cary’s 1989 thoughts on the subject in

1989.

Radio Eireann in

1939 was the chief provider of Irish language broadcasting but this year would

see four different stations in three different countries broadcast ‘as

Gaeilge’. Vatican Radio aired Irish programmes at 7.30pm hosted by the Rector

of the Irish College

in Rome broadcast on short wave for the faithful

in Ireland Germany Ireland Berlin University

who had visited Ireland National Museum Ireland and the Irish Diaspora in Britain

The final broadcaster

‘as gaeilge’ was the IRA’s broadcast station which was located in Ashgrove

House, Rathgar and began all their broadcasts with a speech in the native

tongue usually delivered by Seamus Byrne. The station was raided and closed at

the end of December 1939 bringing the decade to a close.

Labels:

2BE,

2RN,

6CK,

broadcasting,

Communications,

Dail Eireann,

Ireland,

Irish,

online radio,

pirate radio,

Radio,

RTE

Monday, 14 October 2019

1930's Irish Radio Analysis - Part Three. The Catholic Church

The Eucharistic Congress in 1932 was a logistical nightmare for the under resourced Irish radio station 2RN. Despite the fact that station just six years old it carried out a number of major outside broadcasts from across

The first

Eucharistic Congress was held in 1881 under Pope Leo XIII. The congresses were

organised by a Papal Committee for Eucharistic Congresses to increase devotion

to the Eucharist as a part of the practice of faith, and as a public witness of

faith to Catholic population at large. The 31st International Eucharistic

Congress was held in Dublin Ireland

Congresses were

often linked with anniversaries or other events special to Christians and in

particular to Catholics of the country in which they took place. The 30th

Congress which took place in Carthage , Tunis , commemorated the death of St. Augustine Dublin

congress commemorated the death of St.

Patrick , Ireland

The new Irish State Dún Laoghaire Harbour

at the beginning of Congress Week was greeted by thousands along the harbour

piers and the Papal Mass in the Phoenix

Park Irish State had successfully entertained literally

thousands of churchmen and laity who came to Dublin

In 1934 despite

the success of the Eucharistic Broadcasts the New South Wales Press reported

‘Many readers may be surprised to learn that there is not a Catholic

radio station in Ireland Ireland Dublin Vatican

station. Wireless experts have been busy with suggestions since the project was

announced, and these include the provision of a shortwave station and the

establishment of a landline from Italy

It was a source of

frustration for the Church authorities and Catholics in general that the

national radio station did not carry weekly Mass. Belfast

broadcast a Daily Service and a Sunday service from various Protestant churches

across Northern Ireland

Although not

officially an anti Catholic stance, the lack of religion and religious services

was a great source of annoyance for the Church. The Church had been a great

supporter of radio when it first went on air in 1926 believing that ultimately

it would be an extension of its dominance over a subservient faithful

population. This stance seemed to be annually contradicted when 2RN (later

Radio Athlone and Radio Eireann) ceased all broadcasts on Wednesday, Thursday

and Friday of Easter Week up to 1936 when the only silent day was Good Friday.

The church exerted

further influence on broadcasting in Ireland

Saturday, 12 October 2019

1930's Irish Radio Analysis - Part Two. The GAA

The men of the

nation were now able to listen to a broadcast of the All Ireland GAA Finals

live hundreds of miles from Croke

Park Dublin

The GAA would have

an uneasy relationship with broadcasting coming to a head in 1937 with what was

referred to in newspaper headlines as a ‘crux’. Radio Athlone had been

broadcasting the Provincial finals in both Hurling and Football, the All

Ireland semi finals and Finals plus the Railway Cup finals from Croke Park

‘As you informed

on a previous occurrence, the proposal that the broadcaster (commentator)

should be selected by the GAA is not acceptable. It would be the equivalent of

transferring to the GAA part control of the State Broadcasting Service’.

The GAA refused

permission to Radio Athlone to broadcasts the 1937 Railway Cup Finals. Both

sides became entrenched and when Radio Athlone announced that Sean

O’Ceallachain and Eamon DeBarra would be commentating on the All Ireland

hurling final from Killarney, Kerry permission was again denied by the GAA

insisting that a commentator of their choosing be behind the microphone.

Broadcasting the final was even more important as it was the first All Ireland

held outside Dublin in 30 years and the first

All Ireland final to be held in Kerry when Kilkenny played Tipperary

A letter writing

campaign orchestrated by the local GAA committees bombarded the newspapers but

Kiernan held his ground. Both sides disputed the costs involved with the GAA

stating that the director wanted the GAA to pay for the commentator while

Kiernan said that all costs including transport, engineering and the

commentator was being paid for by the State broadcaster.

There would be no

play by play commentary for the 1937 All Ireland Hurling Finals and no

facilities within the ground made available to the broadcaster. Their

alternative was to have their two chosen commentators O’Ceallachain and DeBarra

stand with the crowd and write down their play by play. O’Ceallachain covered

the first half and exited the ground to go to Killarney Post Office where a

microphone awaited and he relayed the game from 4.15 – 4.45pm. DeBarra followed

with second half until 5.15pm. It was unsatisfactory but inventive under the

circumstances.

The blame from the

grassroots was divided with some GAA councils openly criticizing the Central

Council and its president Padraig O’Keeffe. A compromise was eventually reached

for the All Ireland Football finals two weeks later when a compromise

commentator Canon Michael Hamilton, the Chairman of the Clare County Board

agreed to bring the running commentary to the listeners. (ALL Ireland

For the 1938 GAA

season a new voice was heard on the airwaves and would dominate for almost

fifty years.

‘Bail ó Dhia oraibh a chairde Gael agus fáilte

romhaibh go Páirc an Chrócaigh’

Known as the voice

of the GAA for almost fifty years, Michael O’Hehir was born in Glasnevin, Dublin on June 20th 1920 to parents from County Clare Connacht provincial title and later serving as

an official with the GAA Dublin Junior Board and chairman of Civil Service and

St.Vincent’s Dublin GAA clubs. Michael was educated at St. Patrick's National School St. Vincent 's club in Raheny. Michael

became fascinated with the radio when he received a present of one as a child.

He had just turned eighteen and was still a school-boy when he wrote to Radio

Éireann asking to do a test commentary and after the events of 1937 the station

were looking for a new voice that was acceptable to them and the GAA.

He was accepted

and was asked, along with five others, to do a five-minute microphone test for

a National Football League game between Wexford and Louth. His microphone test

impressed the director of broadcasting T.J. Kiernan so much that he was invited

to commentate on the whole of the second half of the match.

Two months later

in August 1938 Michael made his first broadcast - the All-Ireland football

semi-final when Galway defeated Monaghan at Mullingar’s Cusack Park Galway and Kerry. The following year he

covered his first hurling final - the famous "thunder and lightning final"

as Kilkenny beat Cork

Sports broadcasts in Ireland was

still in its infancy at this stage, however, his Sunday afternoon commentaries

quickly became a way of life for many rural listeners who gathered around radio

sets to listen to the games. As a man who could ‘make a boring game

interesting’, by the mid-1940s Michael was recognised as one of Ireland

Thursday, 10 October 2019

1930's Irish Radio Analysis - Part One. Society Changed by the Wireless

Irish Radio in the

1930's was to be educational. Its early aims were to teach farmers how to farm

better and improve productivity holding out the dream of a better way of life.

It would teach new languages including Irish, French, German and Esperanto. It

would help to teach children many of whom had left school early to work the

family farm or just to survive. Radio would provide women more help in the

kitchen, which they rarely left. There was a hope that the station could be all

things to everyone but it ended up being nothing to anyone except those who

could criticise or take monetary advantage. The arrival of radio would alter

the Irish people and their persona more than the introduction of the telegraph,

telephone or even television. Rural Ireland

The monetary value

of radio broadcasts were exploited as village fairs, fetes and charity events across

Ireland

Entertainment was

an escape from the trauma of the battlefield, the poor and distressed living

conditions and the mundane hand to mouth existence of much of the rural Irish

population. In many homes in Ireland Ireland Dublin

What difference

would radio make to the simple, uneducated farmer living in Dingle or Ballina?

Rural Ireland

‘broadcasting will help towards

filling the gaps in the lives of our rural population, which gaps at present

are dull and uncultivated gaps.’

The arrival of

radio made the communal newsreader unemployed as you did not need to read and

write to be able to listen to the news via the wireless and form your own

opinions. There was still the gathering, the social third place after work and

domestic living, but the nature and tone of the gathering had changed. Before

radio broadcasts, entertainment centered on the house party. Locals would

gather, drink perhaps some locally distilled spirit, sing traditional tunes and

sean nos dance on the grey flagged stone floors while maintaining the Irish art

of the storytelling. But now the radio broadcast was the centre of attention.

People listened in silence to the music and the news.

The local

traditional music was not just the only music available to the listener

especially the young and impressionable. Marching band music, Operas, Jazz,

crooning which was invented for radio vied with traditional Irish music for the

listeners attention with the native airs no longer locally based but a national

identity. Musicians from Kerry could now

hear musicians from Donegal and like an accent or a dialect there were often

variations in the way the same traditional tune was played. There were new

influences appearing in traditional Irish music much to the dismay of

traditionalists and purists and for this radio was blamed. It was a diluting of

the traditional and a moving away from the Irish culture and heritage that was

once almost lost and certainly driven underground under Britain Ireland

But now the social

equilibrium was broken as a new voice entered the home. This new unseen voice

was full of new ideas, ideologies and advancements that produced change faster

than the listener could adapt. The radio set was the first piece of twentieth

century technology to enter the Irish home. In most houses even before

electricity the radio set was the only piece of modern furniture. For many

households who bought an imported radio set it was a major investment in tough

economic times.

Women were

suddenly not lonely when their men folk were out in the fields or cutting turf

on the bogs. They were gaining in independence, more receptive to new ideas. The

radio was a window on the world rather than a world that just involved the

people and events of the next town land. The Irish had let this unseen stranger

into their homes in a very intimate way. There were no formal introductions,

their way no way to judge by a man’s looks if he was honest or not. This voice

from the box was invading a space traditionally reserved for the man of the

house even though that person by the act of purchasing a radio set issued an

unwritten invitation. The sense of wonderment that somehow you were listening

to a broadcaster or a musician in Paris, France while you sat in your kitchen

in Kerry was in itself a complicated concept to accept by a simple man from of

the land. If you lived on an isolated farm the only voices you would hear were

those of your family, your neighbours and perhaps a few villagers as you

attended Mass on a Sunday. This totalled less than one hundred people but by

listening to the radio you had doubled that total in one week.

People began to

speak about presenters in the same way they would talk about a family member

even though they would never actually cross paths. Presenters were becoming

household names. There was a third presence in a marriage whether the spouses

liked it or not. The first battle over what should be listened to was now

breaking out. Different styles of music and not just Irish traditional music

was drawing greater audiences. When local musicians came to the house they

played the tunes they knew and same way they always played them but they were

now becoming redundant as with a turn of the dial or a movement of the aerial,

‘new’ music was being heard.

When they heard Birmingham , Manchester , Pittsburgh or New

York

Radio changed the

social activities of the natives. Radio became a national culture and a

disseminator of culture. No longer did people have a parochial or provincial

window on life they were now part of a bigger country or the world Listeners

across the length and breath of the country were able to hear the same music,

talk or news at the same time as everyone else. The advertisement of products

was now a national endeavour rather than a local necessity. Radio became a shared experience with people

they would never meet. There was no need to leave the house to be entertained.

No need to go to the theatre as 2RN broadcast plays, no need for vaudeville as

comedians embraced the new medium and the musical hall came to your living room

rather than the need to travel or pay an admission fee even though a licence

fee was required to listen to the radio but the purchase of licences outside

the urban conurbations was slow. The radio also meant that your entertainment

requirements were not affected by inclement weather. The way we were

entertained and the way we demanded to be entertained reached new plateaus.

The men of the nation were able to

listen to a broadcast of the All Ireland GAA Finals live and we will look as

the new stations uneasy relationship with Ireland’s largest sporting body in

the next post.

Labels:

2BE,

2RN,

BAI,

Belfast,

Communications,

Dail Eireann,

free radio,

GAA,

IMRO,

pirate radio,

Radio,

RTE,

UTV

Saturday, 5 October 2019

'No Borders' Radio in Ireland

Just like it is today the border between the new Irish Free State and Northern Ireland

On December 13th 1927

at 8 pm a unique experiment took place, that at least for forty five minutes united the island of Ireland Belfast Belfast radio station 2BE but in a moment of

broadcasting history it was also relayed by 2RN in Dublin

and 6CK in Cork

The Lord Mayors of the three cities recorded greetings

for each other which were aired before the relay. The Lord Mayor of Belfast Rt.

Hon. Sir William Turner attended the Empire in person and spoke into the

microphone from the stage. The comedy revue was written by Richard Hayward and

Gerald McNamara and was described in the pre-publicity as having ‘seventeen

scenes of fun and frolic’ performed by the Ulster Players. The show was set in

a radio station studio. Some of those who performed in the show were Vivian

Worth, Marian Wright, Kitty Murphy, Dorothy Camlin, Jack Chambers, Richard

Hayward, Jack Gavin and Kenneth Coffey.

While the relay was well advertised in the Dublin newspapers, the Belfast newspaper like the Telegraph and the Northern Whig advertised the show at the Empire Theatre just before it closed for renovations and the fact that it would be relayed on the 'wireless' but did not push the fact that it was being relayed on Free State radio stations.

Labels:

2BE,

2RN,

6CK,

BAI,

Communications,

Dublin radio,

free radio,

IRTC,

radio ireland,

RTE,

UTV

Gardening Shows on Pirate Radio

To follow this controversial show was 'The Gardening Hour', but this was no ordinary horticultural show in fact the show gave an in depth guide on how to grow and cultivate cannabis, and like the lead it show it proved very popular on Speak Your Peace.

Wednesday, 31 July 2019

The Legacy of Irish Pirate Radio

What is the real legacy

of pirate radio in Ireland? As we approach the 30th anniversary of

the Wireless Telegraphy Act and the closing of many of Ireland’s most iconic

and successful pirate radio stations was there more to that period other than

the rosy tinted nostalgia for a pre-social media, fake news and Brexit?

Pirate radio has a long

tradition in Ireland dating back to the 1916 Rising when a rebel radio

apparatus made Ireland the first nation in the world to be declared by radio.

In Britain the pirate radio that created the need for a pop music channel was

located on the high seas with the likes of Radio Caroline but in Ireland the

radio buccaneers remained on dry land. The plethora of pirate radio stations in

Ireland exposed the listening public to the possibility of an alternative to

RTE Radio. It created an awareness of the power of radio and it also

demonstrated to financial giants that radio in Ireland could generate huge

turnovers.

Pirate radio across

Ireland in cities, towns and villages gave a voice to communities and allowed

local businesses to advertise local people. The golden era of pirate radio for

the decade 1978 to 1988 was the birth of a fledgling radio industry that today

directly employs hundreds of people and indirectly thousands in ancillary

service such as transmission provision, PR companies and advertising agencies.

In the late seventies the hobby, bedroom room, homemade transmitter pirate

station was making way for more grounded yet still illegal stations with

imported purposely built transmitters, studios and offices located in Georgian

buildings and formats that were attracting listeners and advertisers.

It created a host of

media personalities many of them still on radio and television today. Household

names trained and mentored on pirate radio. Pirate radio was a beacon of light

in times of local crises. RTE is a national state broadcaster trying to cater

to everyone’s needs and tastes while BLB was Bray Local Broadcasting in every

sense of its title. When Hurricane Charlie struck the seaside town in 1986, BLB

was the glue that held a community together. It informed, it comforted and it

made a difference.

Without pirate radio some

of Ireland’s most famous musicians would not have had a platform for success.

Would U2 have become the global force they have become if in the 1970's and 80's

they were solely reliant on RTE Radio 2 for exposure? Would Daniel O’Donnell

have become the massive star he is without the airplay from TTTR, Radio Star

Country or Mid West Radio?

Pirate radio shone a

light on dull, dark Ireland and for that as a nation we should be thankful and

praise the contribution of all those pirate broadcasters across Ireland we have

made a difference.

Wednesday, 10 July 2019

Early GAA on Television

If you visit the excellent GAA Museum at Croke Park you will see their current exhibition 'Wireless to Wifi' which tells the story of how the media has covered the GAA games since it became the first field sport to be broadcast on radio on 2RN in 1926.

The exhibition lauds the fact that when television arrived in Ireland in 1962, the fledgling RTE covered Gaelic games on television but the history of Gaelic Games on television stretches back further into the early days of television.

In September 1950, the BBC in the midlands of England had cameras and crew on had at Robin Hood stadium to cover the British Hurling Championship game between the local John Mitchels club and the ultimately victorious London's St. Mary's on a scoreline of 4-4 to 2-3. In the newspaper it was described as 'hockey with inhibition' and commentary was provided by RTE's voice of the GAA, Michael O'Hehir. Highlights of the game with shown on a sports round up show the following night.

The exhibition lauds the fact that when television arrived in Ireland in 1962, the fledgling RTE covered Gaelic games on television but the history of Gaelic Games on television stretches back further into the early days of television.

In September 1950, the BBC in the midlands of England had cameras and crew on had at Robin Hood stadium to cover the British Hurling Championship game between the local John Mitchels club and the ultimately victorious London's St. Mary's on a scoreline of 4-4 to 2-3. In the newspaper it was described as 'hockey with inhibition' and commentary was provided by RTE's voice of the GAA, Michael O'Hehir. Highlights of the game with shown on a sports round up show the following night.

In New York following the success of the 1947 All Ireland Final won by GAA, the local GAA committee and the authorities in Croke Park attempted to expand the games on the far side of the Atlantic. This included exhibition games similar to the more recent All Star tours and in the early 1950's the National League Final was payed between the winners of the 'Home' final and New York. These games gained widespread coverage amongst the Irish media in New York but also on television when a local brewer provided the sponsorship to have the game televisied.

In 1948, The Munster Express reported that Waterford played Kilkenny in New York with highlights of the game shown on TV.

From the Irish Independent July 22nd 1950

Wednesday, 26 June 2019

A Century of Irish Radio Reviews

A Century of Irish

Radio 1900 -2000

This new book tells the story of how this popular medium with much of

its early history centered in Ireland, has revolutionised and changed Irish

society more than any other medium.

“An excellent work, this book is a must”, Ian Biggar,

The DX Archive (Scotland)

“An excellent read”, Amazon 5* review by Premier Radio

“If you’ve an interest in broadcasting, this book is

for you. Well worth the money”, Aidan Cooney Q102 Presenter and former Ireland

AM (TV3) host

“Eddie’s magnus opus is the most comprehensive work on the history and evolution of radio in Ireland. Historically important record” Eoin Morgan News4 Newspaper

“A great book”, Ralph McGarry radio presenter

“A great book”, Ralph McGarry radio presenter

“A superb read” E. Burbage on Goodreads

“A great read” Rob Allen 96FM Cork

This comprehensive story begins when Ireland became the first nation in

the world to be declared by radio during the iconic events of the 1916 Easter

Rising. It charts the birth of legal radio in 1926 which is shrouded in scandal

and reports of corruption with fatal consequences. Irish radio while born in

the twenties, the evolutionary 1930's would change how the Irish listener

consumed and interacted with the’ wireless’. The book tells why Radio Eireann’s

revenue in 1932 was £220 but a year later they reported revenues of £22,000. In

the 1930’s you could learn to swim on the radio or listen to commentaries on

the International Fishing competitions held on the rivers and lakes of Ireland.

You can read about an anti-Jazz movement whose legal ramifications are still

felt today and how the Church and State battled both for and on the airwaves.

We unravel an urban myth that the first ever radio broadcast of ‘The Saint’ was

on Radio Eireann in 1940. The book tells the story of the first man in the

world to die on hunger strike, Sean McNeela having been convicted of pirate

radio broadcasting. The book acknowledges the real success of Radio Eireann as

it transformed rural Ireland on limited resources and offered women a new

independence and perspective.

The Irish language was relegated to third place for a time on the

official airwaves but the radio battle for our native language to have access

to the ether has been long, protracted and eventful. Irish radio has been a conduit

for propaganda and has become Americanised with men like Bill Cunningham

changing how we consume radio, the giveaways, the profits and even the success

and failure of Atlantic 252. The book tells how this nation interacts with the

rest of the world through radio and how ironically it was two Englishmen

Leonard Plugge and Chris Cary who revolutionised radio in Ireland.

For the first time ever, the book lists and offers station histories of

over one thousand illegal pirate radio stations from the first conviction of

Michael Madden in 1935 to the commercial successes of the so called super

pirates of the 80’s with Nova and ERI. The book examines the impact of

political pirate radio in Northern Ireland at the beginning of the troubles and

how paramilitary pirate stations brought down a Government and accelerated the

end of a major political career. It documents how pirate radio and TV both

threatened Government policy and led to dramatic change. As an avalanche of

pirate radio stations across the country forced new legislation creating legal

independent radio and television, commercial interests would dominate and cause

further controversy with stories of fraud and corruption.

Learn about the good and evil within pirate radio, how this illegal

activity created today’s radio industry. ‘A Century of Irish Radio 1900-2000’

covers the border blasters, the innovators, the urban myths are dismantled, and

we reveal the careers of characters and presenters from Michael O’Hehir and Larry

Gogan to Dave Fanning and Andy Preston. The first full comprehensive history of

Irish radio in decades is detailed in this 595-page book.

Copies of the book can be purchased here:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)