Friday, 29 May 2020

The Irish Pirate Radio Archives - Airwaves Fanzine

The history of Irish pirate radio is diverse and over the years a number of fanzines were published to promote the various pirates. This is Airwaves edited by Paul Barrett.

Saturday, 23 May 2020

‘The Modern Swash Buckling Pirate Phenomenon’

On any given Sunday on

the Dublin airwaves in 2020, the listener is treated to a melange of radio

stations delivering a wide variety of speech and music entertainment. However,

the Dublin airwaves are a uniquely Irish solution to an Irish problem. Radio in

Ireland is the most consumed form of media with over 80% of the Irish adult

population listening to the medium, whether it’s in the home, exercising or

stuck in the car in a rush hour traffic jam. Because of its unique ability to

connect with its audience, the listenership figures have stayed constant for

the past quarter of a century and as a result, advertisers have flocked to the

national, independent commercial and local radio stations across Ireland.

The Broadcasting

Authority of Ireland issues licences for the independent sector, advertising

different genres to accommodate all tastes. This radio industry we have today,

was born in the 1970’s and 80’s when the state broadcaster RTE, had its

monopoly position challenged by a plethora of pirate radio stations, stealing

frequencies, listeners, and advertisers from RTE. In 1988 new stringent

legislation plugged loopholes in the law and allowed for the orderly opening of

legal licensed alternatives both nationally and locally. The BAI, and its

predecessors the IRTC and BCI have struggled to blend listener requirements

with commercial demands. Since deregulation in 1988, the market has solidified

with some major media moguls commanding ownership of vast swathes of the

airwaves.

In the eighties the

success of the pirates was driven by market forces as a youthful market

demanded to hear the music that they wanted, a direct alternative to RTE, who’s

darkened halls attempted to accommodate everyone on a national level when listeners actually

wanted a local voice and perspective. RTE had failed the younger listener and

even with their attempt to placate that constituency with the launch of the

‘pirate light’ RTE Radio 2, the uplifting super pirates like Radio Nova,

Sunshine & ERI dominated their markets. In the quest for the local

listener, once again RTE lost out to community stations like BLB and Kilkenny

Community Radio and local stations like Mid-West and West National Radio 3

rapidly eroded any credibility RTE had with its listener.

Licensing has regulated

the airwaves is the Government response, but even a cursory glance along the

waveband on a Sunday tells a different tale. When the pirates were at the

height of their success, every genre of music was catered for by individual

stations, pop on Nova, rock on Phantom, C&W on TTTR, religion on ICBS or

album tracks on Capitol. Today’s youth population listens to their music,

dance, garage, trance, and rap but these music trends do not sell advertising

and therefore find every little light on the current station playlists. That

demographic is younger, usually under eighteen and therefore unimportant to

current stations and their advertisers. Once again in step the pirates and as

enforcement retreats like the tide, the pirates are empowered to start up their

transmitters once again and fill up the Dublin FM frequencies. Not only has a

need been created for these stations but technology has made it easier to get

on air. Gone are the days of medium wave transmitters, home built, strewn over

an attic floor with an aerial strung between the attic and a tree or telegraph

post. FM transmitters are cheap and highly effective. They do not cause the

interference that their Medium wave forbearers did, and computerisation has

removed the need for bulky turntables and mixing desks. Because of their appeal

to an under eighteen audience, these stations utilise social media avenues far

better than their legal counterparts.

In Dublin on FM on a Sunday there are a number of national and quasi national stations like

RTE, Radio na Gaeltachta, Newstalk and Spirit Radio, there are community

stations including Dublin City FM, Near FM and Phoenix Radio and there are five

legal local franchises 98FM, Radio Nova, Sunshine 106, Spin 1038 and FM 104 all

competing for the listeners ear and you would say to yourself that surely that

is a comprehensive choice but yet despite five Dublin licensed stations, on

Sunday April 19th 2020 there were thirteen pirates radio stations on

FM, one on Medium Wave, Energy 1395 and four on short wave broadcasting to the

world. The majority of these pirate stations were broadcasting some form of

dance music but other genres were being catered for that licensed stations

seemed to have covered but yet pirate station were on the airwaves covering

similar including The 90s Network and Easy FM.

Some legal stations are

now voice tracked removing that personal touch with the listeners. This is

simply a cost saving exercise for the media conglomerates that own them. This

would be obvious if they used in studio cameras like watching RTE’s Today

programme with the now retired Sean O’Rourke. A camera could show the DJ actually

choosing and enjoying the music he is playing. The pirate DJ is not hampered by

the playlist or the format. The reasonable pirate example of this is Phever FM.

The inertia caused by the

lack of enforcement has given pirate radio a new lease of life with a number of

them including Club, Pure and Pirate FM carrying a significant amount of

advertising, not just relying on advertising club nights to generate revenue.

Despite the coronavirus lockdown, the closure of venues and therefore the

closure of those station revenue streams, the FM band is alive with pirate

radio. These stations are catering for audiences ignored by mainstream stations

who have once seen themselves as cutting edge, but the commercial reality has

diluted their position. None of these pirates broadcast salacious, threatening

or terrorist content and are simply on-air to entertain their constituency,

they give airtime to new and struggling dance and rap artists and without

causing interference they do little harm. They are however illegal and subject

to a minimum of €10,000 fine either for broadcasting, advertising or providing

transmission land and if Comreg continue to not implement the law and the BAI

fail miserably to cater for the people who are actually listening to the radio,

not the listeners that stations wishes to portray to advertisers, then pirate

radio will continue to blossom. Is it too early to claim ‘long live the

pirates’?

Friday, 22 May 2020

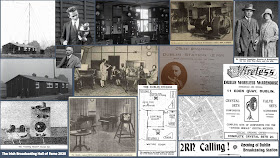

Dublin's Pirate Radio Stations of the Early Twenties

The Irish Free State authorised 2RN to become the State’s official radio

station and on January 1st 1926 it would officially go on air. Irish listeners,

especially those on the East Coast, were already avid listeners to the new

medium of radio. The sales of wireless sets had blossomed, with businesses like

Hogan’s in Henry Street, Dublin supplying imported sets to those who could

afford them. For those who could not afford them, a homemade crystal set gave

them access to the airwaves. Listeners were entertained to broadcasts by

London, Newcastle, Cardiff and Manchester amongst others. Following the

formation of the new state, there was a divergence from the British laws that

governed life in the country. Many of the laws were embraced by the Government

including the British 1904 Wireless Telegraphy Act. Then in February 1924, the

Irish Government implemented a licensing scheme for radio sets which was to be

collected through the post office.

For many listeners south of the border, the arrival of 2BE in Belfast in

September 1924 increased the urgency of having a Southern voice but there was

division within Government circles as to whether the Free State’s venture

should be commercially and privately run or State operated. In the end 2RN was

a State body.

Many amateurs were building crystal sets to listen-in, but some

inventive radio engineers were discovering that it was easy to turn their

listening devices into transmitting devices. These amateurs were warned by

newspaper columnists like ‘Radio Rex’ and ‘Jack Broadcaster’ that this was

illegal and they should desist.

The so-called experimenters who were in actuality ‘pirate radio

stations’ outside the law, were rebroadcasting British stations received on sophisticated

sets in order that the amateur built crystal sets would be able to pick up a

signal. This too was referred to in the newspaper columns with one declaring

that,

‘Now I am informed that some people in what

may be described as misplaced kindness are endeavouring to re-radiate received broadcast from

their aerials to those of nearby crystal users. This is

absolutely illegal and must on no account be attempted. You are not

allowed to transmit. I shall be glad to assist those who try to locate

offenders.’

On January 18th 1923 in The Evening Telegraph, readers with

an interest in radio was left in little doubt as to the legalities of

‘broadcasting’ rather than listening. It advised,

‘The position of the Free State in regard to

the question of broadcasting, it may be taken for granted that broadly stated

(1) Broadcasting of any kind is not legal yet in the Irish Free State. (2) That

any instruments for the purpose of broadcasting are illegal. (3) That any

attempt to bring in such instruments would be frustrated, the instruments of

discord on-route would be sequestrated.’

Despite this information, an unusual pirate broadcaster turned out to be

an attempted fraud and was exposed on the front page of the Evening Telegraph

in November 1923. An authorised radio set dealer became aware of fraudsters who

were selling sets at an unbelievably cheap price, purporting to receive all the

British stations. He made an appointment to view the set and when the seller

turned it on, he said that they were tuned into the Manchester station 2ZY.

They listened to gramophone records and an announcer. After a period of

listening the scam unravelled as the authorised dealer said that the announcers

voice had a distinct Dublin accent. All was then revealed. The scammer and his

confederate had set up a pirate transmitter nearby and was broadcasting the

records and using a crude microphone to deliver the announcements pretending to

be 2ZY. The ‘wireless set’ that they were trying to sell would barely be able

to pick up a station that was just twenty miles from the receiver, it only

contained a single value. The uncover

businessman remarked to the reporter that

‘The amusing part was that he had a rather

clumsy contraption fitted up with the idea of humbugging innocent people into

believing that the results obtained on his 'single valve set with a frame aerial

were better than any of the demonstrations by the big wireless firms.’

He added

‘This kind of work is very good for

experiments, but when it is done for the purpose of leading people to believe

that they are listening to an actual station broadcasting, well it does general

wireless work harm, first by making people suspicions and secondly by

disappointing them by bad results.’

One pirate station seemed to make a genuine attempt to become the

‘Dublin station’ in advance of any officially sanctioned station. In May 1924,

‘The Grand Central Station Dublin’ was heard on the airwaves of Dublin on 390m

medium wave. Reports said that on some of its broadcasts it suffered from

interference from 2NO in Newcastle. The station broadcast from 9pm – 9.30pm.

The ‘Dublin Studio’ as it deemed itself was located Northside of the city and

introduced its pirate transmission with the announcement ‘calling Dublin,

Glasnevin and everybody’. One writer to the newspapers wrote a critique of the

broadcasts and offered some advice,

‘I would recommend that he is again whistling

‘Father O’Flynn’ for broadcasting that he should not blow directly into the

microphone, as the result last night was more rushing wind that musical.’

The station carried on intermittently throughout the rest of the year

with various reports appearing in trade magazines. They appeared to be coming

from the one station although there were many experimenters as the frequency

used was regularly on 390metres. In January 1925, The Radio Digest magazine in

the United States reported in its ‘European Notes’ section that,

‘broadcasting is being carried out nightly

from an unknown location near Dublin, Ireland, much to the annoyance of the

Irish post office authorities who have been unsuccessful in their attempts to

locate the illegal station’.

Pirate radio would be a thorn in the side of the authorities throughout

every decade up to the present days with many pirate radio stations still

taking to the air.

Monday, 18 May 2020

The Irish Pirate Radio Rivalries - Of the 1930's

For many, the great pirate radio rivalries in Ireland were ERI and South

Coast in Cork, Nova and Sunshine in Dublin in the 1980’s or the Radio Dublin

and Alternative Radio Dublin’s battles from the seventies but a pirate radio

rivalry erupted on the airwaves in the 1930’s between stations in Limerick and

Waterford.

The 1926 Wireless Telegraphy Act was introduced in November 1926, nine

months after the official launch of 2RN. The Act would regulate the airwaves,

write the rules on licence fees and deem what should and should not be

broadcast. The Act was supposed to be a deterrent to illegal broadcasting but

that did not stop illegal stations broadcasting taking to the airwaves. One man

in Limerick would break all the rules. Jim O’Carroll attended the Technical

Institute on O’Connell Avenue in the city and developed a keen interest in

electronics. As a result while experimenting, he built a crystal receiving set

that allowed him to listen to 2RN, the BBC and with improvements he began to

listen to Short Wave broadcasts from America and Australia.

In early 1935, O’Carroll added an oscillator to his receiving set and

turned it into a crude transmitter that was powerful enough to be heard all

over the city. After testing its limitations, O’Carroll had to find a home for

his new station, as living with his sister was not an ideal location for

secrecy. He eventually found a location on the third floor at the home of his

friend Charlie O’Connor at 84 Henry Street. The station began broadcasting in

February 1935 on 360m, very close to the powerful transmitter in Berlin,

Germany broadcasting on its allotted frequency of 356.7m, which meant that both

signals interfered with each other and

often the Limerick station had to wait until the Berlin transmitter was turned

off to get a good signal out across Limerick City. By April, reports of a Limerick

‘Mystery Station’ was reaching the national newspaper headlines.

The station was now named The City Broadcasting Station (CBS) as O’Carroll

had been listening to CBS broadcasts from across the Atlantic and liked the sound

of the name. He went on the air playing whatever gramophone records he could

lay his hands on. On the air most nights from 7.30 – 10.30pm, the station

continued with Billy Dynamite (O’Carroll) and Al Dubbin (O’Connor) at the

controls broadcasting a mixture of speech, gramophone records, and relayed

programmes from American radio, including the news and even swimming lessons on

the radio.

The Limerick Leader reported on April 6th,

‘The

operation of a mysterious broadcasting station in Limerick for some past time

had the citizens and officials agog. Listeners-in are occasionally startled

when they hear an unofficial announcer make reference to local matters and some

well-known personalities.’

The Liberator newspaper in Tralee on the same day reported,

‘The annoyance caused

by this is distinctly perturbing to owners of sets.’

The appearance of CBS on the airwaves of Limerick was greeted by a

variety of different headlines. The Irish Examiner (6/4/1935) headlined their

article ‘Wireless Nuisance’, The Kerryman (13/4/1935) spoke of a ‘Secret Radio

Station’ while the Irish Independent described them as the ‘Mystery Station’.

The station continued from February to October with the only change being its

location, when the station moved to the home of Michael Madden at 25 Wolfe Tone

Street who had been providing the batteries for the station’s transmitter. The

station went from strength to strength and became the first station in Ireland

to carry a paid commercial rather than the sponsored programming aired on the

national station, when the Wolfe Tone Dairy began to advertise its products.

The owner of the dairy was John Toomey, who ran a successful

grocer/dairy/vegetable shop and was the proud owner of an ice cream machine,

selling homemade ice cream cones. Summer was coming and ice creams would be a

popular seller. O’Carroll said after,

‘As

I began to get a little bolder, I discreetly canvassed for commercials. My

first contact was the owner of the Wolfe Tone Dairy, Mr. Toomey. He had a fine

grocer's shop but, in addition, he made delicious ice cream on the premises. I

told Mr. Twomey that I knew a man who could contact the elusive Pirate and

arrange to have his delicious ice cream mentioned on the air. He was to make no

payment until he heard the broadcast. He offered the incredible sum of £10 if I

arranged this transaction. Ten pounds was about a month's wages at the time.

For a schoolboy one could almost retire! Needless to remark, as far as I know, that

was the first radio commercial in Ireland.’[1]

There were queues down the street for the ice cream encouraging John Toomey

to invest in a second machine to keep up with the demand.

‘An

enduring sight in my mind's eye is a very long line of people reaching in the

direction of what was then Gleeson's public house waiting to purchase cones and

wafers from a delighted Mr. Toomey[2]’

said O’Carroll

The

station began carrying ads for Clohesy’s Pub on Charlotte Quay, one of the most

popular pubs in Limerick at the time. O’Carroll also added in an interviwe with

the Limerick Leader in 1976, that

‘a committee running a

sports outing in Castleconnell asked us to advertise their sports meeting, we

had a ‘What’s On Guide’ in Limerick cinemas’.

The advertising revenue was beginning to pay

off for the radio entrepreneurs. The station would carry local news bulletins

and because they broadcast late at night, they would collect the following

morning’s national newspapers arriving in Limerick railway station at nine o’clock

and broadcast the headlines for their listeners much to the displeasure of the Irish

dailys, and this was replected in their coverage of the station.

Meanwhile in Waterford City another broadcaster was taking to the

airwaves. The ‘Waterford Broadcasting Station’ was heard broadcasting on 280m

medium wave and were on air from 11.15pm for an hour. On Wednesday April 17th

, the broadcast to the listeners of Waterford, which was described by the Irish

Independent correspondent as ‘a most enjoyable broadcast’, included ‘gramophone

records, vocal and instrumental items’ but ended with an unfavourable critique

for their Limerick rivals. The announcer bemoaned that,

‘an

amateur in Limerick had broadcast programmes which were injurious and

objectionable.’

He added,

‘I would

like listeners to understand that I disapprove wholeheartedly and condemn

abuses by this amateur of the powers his transmission station gives him’.

The spat over the airwaves reached the newspapers the following day when

the Irish Press on their front page headlined ‘Another Mystery Station, Radio

Rivals’. Some of the issues related to newspaper reports that O’Carroll’s

signal was interfering with listeners enjoyed of concerts from the Berlin

station.

Further broadcasts from the Waterford station were noted on July 28th

at 2pm, when a thirty -minute broadcast of music was interspersed with

announcements in Irish that there would be further broadcasts to follow.

In Limerick on October 31st, Halloween, while Michael Madden was on the

air, the station had been tracked down and was raided by the police and an

engineer from the Post Office Walter Dain. Madden was arrested and the

equipment confiscated. O’Carroll partly blamed the raid on Madden himself, who

had been drinking in local pubs boasting the fact that he was ‘the radio pirate’

and that information was relayed to the Gardai in Limerick. O’Carroll was in

Dublin on the day of the raid visiting his mother and the day after the

Limerick raid his mother’s house in Milltown was ‘ransacked’ according to

O’Carroll as Gardai searched for links to a suspected IRA transmitter that was

also broadcasting in Limerick.

Even before the court case following the 1935 raid had reached the

courts, a radio station was reported on the Limerick airwaves in early February

1936. The station was advertising a local dance and encouraged listeners to

support the event. Following a court case on February 28th 1936 Madden was

convicted and fined £1 and 2 guineas costs. During the case Garda Lenihan said

that,

‘during the illegal broadcasts names were mentioned and scandalous

remarks used’.

It would be the first conviction under the 1926 Wireless Telegraphy Act.

In June 1936 another station was reported by the Irish Independent as

being on the air, calling itself ‘The Curraghrock Station’. The newspaper

reported two females were heard on air followed by a gramophone record

programme. By July 1936 the tone of the station was causing problems for the

authorities in the Limerick area and in Government circles in Dublin. The issue

for the authorities this time was more urgent as the broadcaster was now

broadcasting IRA propaganda. The announcer was reported as telling listeners

that the station was set up ‘to disseminate Irish republican Army

propaganda’. This time the station used

a frequency used by the Munich station and again like the station the previous

year would have a better range once the Munich transmitter fell silent. The

station was probably located in the Barrack Road area hence the confusion in

the name as there is no ‘Curraghrock’ in Limerick.

This station was seized on September 4th 1936, when a house

on Newnham Street was raided by Post Office Engineer William Carroll and Garda

Lenihan. Despite this raid, another Limerick pirate transmitter was back on the

air by September 16th, on the 360m frequency ‘treating listeners to

a programme of gramophone records’ but while there were announcements, there

was nothing of a political nature.

At the subsequent court case on December 4th, Edward Quin of

Clancy Strand was prosecuted for maintaining illegal transmitting apparatus

contrary of the 1926 Wireless Telegraphy Act. The State prosecutor stated that

the items seized were,

‘one

medium wave oscillator, one low frequency amplifier, one carbon type

microphone, and one short wave oscillator’

Garda Lenihan stated in

evidence that Quin tried to pocket a value from the transmitter which he later

claimed he took because he had it sold and didn’t want to lose it. Lenihan

disclosed that he had spoken to Quin on a number of previous occasions about

the need to stop illegal broadcasting. All the wireless articles found in the

house were produced to the Court and the GPO engineer Thomas Carroll then

described what had to be done to test the-apparatus. The test broadcast worked ‘quite

satisfactorily’. According to a GPO Inspector he had received a test message

from the transmitter and the ‘message was quite distinct’. His finding was

corroborated by another engineer Mr. T. White. The prosecution was determined

to achieve a conviction and were willing to call several experts to ensure the

result. They wanted to send out a message to propagandists who wished to use

the radio waves to propagate their messages that they would close them and that

the only broadcaster allowed to broadcast in the Free State was Radio Eireann.

While Madden and O’Carroll in Limerick were pirate broadcasting for

entertainment purposes, a more sinister type of broadcasts had appeared on the

airwaves in Dublin. On Friday October 25th 1935 at 2.30pm listeners

on medium wave reported hearing a ‘mystery transmitter’ announcing that it was

‘Radio Phoblacht na

hEireann, The IRA broadcasting studio.’

The station’s announcer gave a lengthy statement on the Irish

Sweepstakes and announced a list of winners. The station then played some

gramophone records including those of the famous Irish born tenor Count John

McCormack. The broadcast lasted about

forty minutes. But the illegal broadcasting of entertainment programmes or

occasional broadcasts from subversive organisations would become the least of

DeValera’s problems as the nation faced into neutrality during the Second World

War.

Greater rivalries would consume the Irish airwaves in the decades to

come but these stations proved that the battle for hearts and minds on the

radio could consume time and newspaper columns.

[1]

From an article by Jim O’Carroll on Limerickcity.ie

[2]

In O’Carroll’s story John Toomey was written as ‘Twomey’ but his death notice

in 1951 denoted Toomey as the proper spelling.

Monday, 11 May 2020

Supporting Pirate Radio Through the Decades

There were a number of

umbrella groups formed to support and lobby for free radio in Ireland. One of

the earliest was an Irish branch of the Free Radio Association that opened in

1968. The Irish branch gave an address at Library Road, Shankill, County

Dublin. Next in 1970 was the United Stations Network which oversaw publicity

for four stations Radio Eamo, Radio Galaxy, Radio Caroline and Radio Baile Atha

Cliath. Their spokesman was Cork born Hugo Riordan. A former Arts student he

was heavily involved in the occupation of 45 St Stephens Green to protect it

from demolition.

The Irish Radio Movement

(IRM) was founded in 1973 to support the growing number of pirate radio

stations and to lobby for alternative radio. When letters to the newspapers

began to appear, they were signed by Ken Sheehan with an address on Mourne

Road. The club secretary would become one of the most well know broadcasters in

Dublin, Mark Storey. In January 1976, the AGM of the organisation was held, and

Paddy Brennan was elected as President, Mark Storey continued as Secretary and

Ken Sheehan appointed Press Officer. The IRM’s also appointed John Dowling as

editor of the group newsletter ‘Medium 6’. The group was disbanded in late 1976

to be replaced by the Free Radio Campaign.

The Free Radio Campaign

was run by Kieran Murray from his home in Ranelagh. The FRC began in 1976, initially

publishing the ‘FRC Newsletter’ in 1976 and 1977 before it was renamed ‘Sounds

Alternative’ in August 1977. The FRC continued until mid 1981.

Anoraks Ireland was based

on Collins Avenue West on Dublin’s northside and was run by Paul Davidson (real

name Tony Donlon). He produced a newsletter, station lists and supplied tapes

and mechandise from the many stations across Ireland. In 1983, in his

newsletter Mr. Davidson reported that he was having issues,

“Anoraks Ireland have

recently been experiencing a number of problems. We are pleased to report that these

have been sorted out. On October 31st the following statement was issued.

‘Dear

Friends, We regret that Anoraks Ireland has been unable to reply to your many letters

in the last four months as we have had serious problems with the continued operation

of Anoraks Ireland. 'Certain people' who do not wish us well have endeavoured

since August 1983 to silence Irelands one and only Free Radio Organisation.

These people have attempted at various times to persuade, discredit and threaten

the existence of Anoraks Ireland by personal visits, the use of a PO Box number

purposely in our postal district area and their latest ploy was to report

Anoraks Ireland to the income tax authorities in Dublin. The inspectorate have

investigated Anoraks Ireland in depth and are satisfied that Anoraks Ireland is

a non-profit organisation run by Radio enthusiasts promoting independent radio

in Ireland.

We

have resisted all threats from these people who claim a genuine interest in

Irish Free Radio, but who are instead motivated by Self Greed and commercial

profit.’”

RTE Created the Irish Pirate Radio Phenomenon

There were many reasons

for the explosion of pirate radio in Ireland in the 1970's and 1980’s. One of

the main reasons was the increased younger population, the children born in the

sixties whose musical tastes were not being catered for by the State

broadcaster RTE Radio. For listeners it was hard to listen to radio when it

wasn’t there. In the 1970’s RTE was hit by a number of workers strikes putting

both radio and television off the air. From 1970 to 1978, there had been more

than a half dozen strikes that either curtained its transmissions or on two

occasions blacked out both radio and television for three weeks each. This was particularly

hard felt as there was only one radio and one television channel.

Mary Kenny writing in the

Irish Press February 2nd, 1970 articulated

‘I

knew there was a strike on at R.T.E. because I found myself listening to The

Jimmy Young Show on B.B.C. Radio 2 in the mornings, smiling at his chuckly

quips and cuddly, presence and painstakingly taking down the abominable recipes

and wishing we had something as inoffensively yet cleverly cheerful.’

For the younger

generation desperate to hear some modern music were relegated to 45 minutes

from Larry Gogan from 11pm, Monday to Friday, nothing at the weekends. This was

yet another opening for the advance of pirate radio to deliver the content that

the youth of Ireland wanted to hear. But a huge amount of credit must be delivered

to the corridors of Montrose itself for the growth of pirate radio. Dublin and

the East Coast of Ireland was well served by radio broadcasts especially from

Britain’s BBC Radio 1 and Radio Luxembourg but as you travelled across the

country these signals faded as did the choice for pop broadcasts. Much of rural

Ireland had no other choice other than RTE Radio (previously known as 2RN) but

in stepped RTE itself. Originally conceived as an attempt to illustrate their

ability to deliver local radio, RTE Community Radio would launch in 1975 with

Radio Liberties in the heart of Dublin their first port of call.

The concept, originally credited

to the then Director General of RTE George Waters, was to take a mobile studio

and a low powered transmitter to towns and villages across Ireland, teach

locals how to present and produce local programmes for its limited transmission

times and all powered through a low powered transmitter on a frequency allocated

to RTE by the European Broadcasting Union, 202m medium wave. This medium wave

frequency would later be augmented by a FM outlet.

Towns would organise a ‘radio

committee’ and ask RTE to choose their town for the arrival of the mobile

station. For many years the man tasked with being the go between with RTE and

the committee was Paddy O’Neill. Paddy was born near Skibbereen in County Cork

and after a brief career as a national schoolteacher he became involved in the

Abbey theatre from where in 1951 he joined Radio Eireann. At the station he

became a producer, one of his most influential roles as producer of the popular

Din Joe’s ‘Take the Floor’. Paddy was also a greyhound enthusiastic both racing

them and being involved in the organising of races. Under the alias ‘Paddy O’Brien’

he became Radio Eireann’s greyhound racing commentator later taking up the role

of Chairman of Bord na gCon in 1983.

Paddy’s role with

advancing community radio meant that he travelled Ireland to make initial contact

with the radio committees, offer advice, training and technical know-how. The interest

created in these towns and villages showed that there was a demand for a local

voice on the airwaves. The committees did not always run smoothly as in 1991

the Ballina Community Radio Committee were been branded 'a snob job' by the

Urban Council Chairman, Gerry Moore who led a high-powered campaign to have the

Committee broadened to one representing all the people of Ballina. When the

Committee input into the Local Radio experiment, planned for Mayo

during June, was set-up, the Urban Council, Trades Council and many other

leading community groups were "snubbed", said Cllr. Moore.

For younger people in

these rural areas, they were often excluded from these daily four-hour

broadcasts and there was certainly rarely little room for modern music. In 1978

the service was advertised as ‘carrying programmes will go out on the medium wave

and items dealing with matters of health, sport, history, music/drama,

education, art, agriculture, planning and development, family finance, youth,

poetry/essays, Irish, quiz, as well as news, will be covered’ no music for the

youth of the community. They wanted to be involved, they wanted to hear their

voices, their concerns and their music and while the ‘committees’ set about organising

for the arrival of RTE’s mobile unit, the more astute set about piggy backing

on the interest created by the arrival.

While there was an official

committee, they were also a ‘unofficial committee’ working in the background. Transmitters

were procured, equipment sourced and DJ’s readied. In many towns and villages

they waited patiently for the RTE van to arrive, do their thing and leave and then within hours or days of that departure the new pirate transmitter was turned on, often

on a frequency not far from RTE’s 202m location so that listeners could find them easily. Financial considerations also

played a role. For RTE’s Community Radio service carried no ads, it was funded

by local donations and business subscriptions, pirate radio would not have the same constraints

and the commercialism of radio would make money for those organising the swash

buckling operations to the detriment of revenue generation for Montrose. RTE

had created a monster.

Further Information

Tuesday, 5 May 2020

When A Radio Station Isn't A Radio Station

Through the pandemic of 2020, radio has proved to be vital in both delivering information and entertainment. Radio is still king. But as we hurtle through the early part of the twenty first century, the discussion as to what exactly the definition of radio is, has taken centre stage and led to differing opinions. For decades radio was delivered through a transmitter on various wavelengths and frequencies but today, what is described as ‘audio content delivery’, reaches our ears via analogue radio, digital radio, podcasts or online radio apps. But while we discuss today was a radio station is, that same discussion could have easily taken place in the late 1970’s.

Like today, the image we

have of radio, is a studio with a presenter behind the microphone and the

content then fed into a transmitter, to broadcast through the ether to your

radio set. But in the 1970’s and early eighties radio came advertised in

different forms, on air with everything except a transmitter, thus avoiding any

law breaking and being deemed a pirate radio station.

There were numerous

different varieties of operations that called themselves ‘radio’ but were not

in the purest sense of the word.

Firstly there was the ‘Festival

Radio Station’. In many rural towns and villages, the highlight of the social

calendar was the local festival or fete, attracting both locals and tourists. These festivals ranged from accordion,

Wild Boar, Trout, May Day, Christmas shopping to Cheese promotion festivals. The

promoters of these festivals advertised a ‘radio station’ to entertain and

inform but rather than transmitter based these stations like Omagh Festival

Radio, Athlone’s and Carrick-on-Shannon’s celebration of the River Shannon and

Radio Loughshinny were ‘broadcast’ via a public address systems attached to

poles in the town or from speakers hung outside the festival office.

Secondly came the Hospital Radio stations. From the 1930’s hospitals

installed speakers and later as technology evolved, bedside headphones so that

patients could be entertained. Initially these systems piped Radio Eireann through

the cables but then hospital specific studios were set up to broadcast within

the hospital. These proved extremely popular with most major hospitals having

their own ‘radio’ station. Hospital radio was extremely popular in Northern

Ireland.

Next came school based radio stations. As the interest of the younger

generation focussed on radio for entertainment and as transistors became more

widespread, with these transistors often tuned into pirate radio stations, school

authorities tried to tap into this interest by allowing pupils set up their own

‘radio station’ to broadcast at lunchtime through intercom systems. A number of

these students would later become involved in pirate radio and would trace

their interest in ‘radio’ broadcasting back to those early school stations.

By the seventies, ‘radio’ was everywhere and with the state broadcaster

Radio Eireann attempting to cater for all tastes, the need for the broadcasting

of popular programmes and music was growing rapidly. Pirate radio offered one

alternative, but others emerged. When President Erskine Childers opened the

expansive entertainment complex of Leisureland in Galway, one of its attractions

was its very own ‘radio station’ broadcasting through the centre’s ‘closed

circuit’ system. It paved the way for other venues to follow the example and

these stations provided an alternative, employment and training for future

broadcasters.

Another ‘radio’ station that gained widespread publicity was CIE’s radio

train. The first excursion departed Kingsbridge (now Heuston) Station on November

6th !949. The idea sprung from two CIE employees Pat Heneghan and Gerry

Mooney and was designed originally to make the centenary of the opening of the

Dublin to Cork rail link. A studio was installed in one of the carraiges and

the ‘broadcasts’ were piped through the train. On that first trip the man ‘spinning

the discs’ and entertaining the passengers was Terry O’Sullivan. The trip was

an instant success and every year throughout the fifties the number of trips of

the Radio train increased and were often sold out. It proved just as popular as

CIE’s other novelty trips ‘The Mystery Train’. The company also ran specials including

an Irish language return trip to Galway and a Pioneers trip with the bar carriage

removed. The bus service attempted to piggy back on the success of the trains

by advertising a ‘Radio Bus’ but it was simply a guide on a microphone telling

some stories and inviting passengers to sing.

Later incarnations of radio stations with the transmitter included the

Virgin Record Store on Aston Quay that opened in the late eighties and stations

built into new shopping centres to entertain and promote the shops in the

centre.

Monday, 4 May 2020

The Not So Long Arm of The Law

The mere nature of pirate radio broadcasting was that you were breaking the law. The authorities did

not want you on air and to effect your departure raids took place. Often a raid would suffice to have

the station at least lay low for awhile but in order to send out warnings to others, court cases

followed and station operators were fined a paltry amount which rarely served as a deterrent.

Occasionally the pirate stations found themselves further up the court chain other than the District or

Circuit Courts. From time to time the names of the illegal pirate radio stations found themselves

been spoken of in the hallowed corridors of both the High Court and even the Supreme Court. Here

are some of the High Court appearances of pirate stations from 1978 - 1988.

not want you on air and to effect your departure raids took place. Often a raid would suffice to have

the station at least lay low for awhile but in order to send out warnings to others, court cases

followed and station operators were fined a paltry amount which rarely served as a deterrent.

Occasionally the pirate stations found themselves further up the court chain other than the District or

Circuit Courts. From time to time the names of the illegal pirate radio stations found themselves

been spoken of in the hallowed corridors of both the High Court and even the Supreme Court. Here

are some of the High Court appearances of pirate stations from 1978 - 1988.